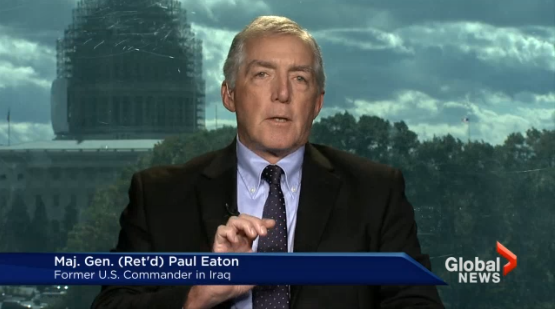

Major General Paul Eaton (Ret.) on Iraqi Soldiers

![U.S. Army Spc. Laurence Walker, left, and Army Sgt. Jacob Ford, instructs an Iraqi soldier how to use a mortar system, Mahmudiyah, Iraq. [U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Kani Ronningen, 4/26/09]](/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/US-forces-train-Iraqi-forces-1024x681.png)

U.S. Army Spc. Laurence Walker, left, and Army Sgt. Jacob Ford, instructs an Iraqi soldier how to use a mortar system, Mahmudiyah, Iraq. [U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Kani Ronningen, 4/26/09]

Building Legitimate Soldiers in Iraq

We are witnessing the unraveling of Iraq’s military and police units in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul and in several cities to the south along the main avenue of approach into Baghdad. The speed of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) assault on the second largest city in Iraq has stunned the command and control structure of the Iraqi Armed Forces and created a leadership vacuum that has destroyed the good order and discipline of deployed Iraqi soldiers and police. In short, the will to fight in many units has been broken.

How did we get here after the United States spent so much in lives and treasure on the development of Iraq’s security forces? And what can we do now that they’re faltering?

Developing soldiers, in the United States and elsewhere, is not a mystery. Essentially, soldier development consists of three major components. We develop the young men and women physically to the point that they feel they can endure any hardship and dominate their environment. We simultaneously impart all those skills that soldiers need to execute the missions that they will receive. The skill sets include how to handle the tools of warfare, weapons, communications and those machines that we will ask the soldier to manipulate. We also teach how to move on the battlefield, how to maneuver, and how to use the tools of war to dominate terrain or enemy forces, or both. Finally, there is what my British colleagues refer to as the moral component. In short, this is the belief in national and military leadership, national institutions, the chain of command and the complete fabric into which the soldier is inserted – that if lost, he will be found, that he will never be abandoned, or, if hurt, he will be medically evacuated. Soldiers will do remarkable things and face great odds if they believe in all these things, and will demonstrate the will to persevere. In other words: military resilience.

When we began the Iraqi Army training program in June of 2003, we conducted a cultural assessment of our complex Iraqi population and crafted a program to cultivate the three components of soldier development. We decided to bring on board retired senior Iraqi military as advisors and developed a program of instruction for our recruits designed to develop Infantry battalions. Finally, we organized our units to reflect Iraqi society down to the platoon level (35 men): 20% Kurd, 60% Shi’a Arab, and 20% Sunni Arab.

Our Iraqi troops proved to be very willing, good students and took on the physical training well and the military training with great interest. However, whereas the moral component is usually easy to develop in Western democracies where citizen soldiers have great faith in the fabric of their society and institutions, this proved to be a challenge in a society coming out of decades of Saddam’s despotism where the forces of tribe, ethnicity, and religion often overwhelm nationalism.

Two anecdotes illustrate this: In a visit to Jordan to encourage a Jordanian Army alliance in our project, I remarked on a pin my counterpart had on his uniform, the Jordanian flag with the numeral “1” superimposed. My Jordanian friend explained that the pin was the King’s idea. It meant “Jordan first,” above family, ethnicity, religion, tribe – all those influencers that can get in the way of allegiance to the state and constitution. Another was my experience at the firing range one day at our training base at Kirkush, where I lay down next to a young Iraqi soldier and introduced myself as the commander. My Iraqi colleague in turn introduced himself and added that he was an Azidi – essentially the same as if I had introduced myself as, “My name is Paul, and I am a Methodist.”

Our work was to get the Iraqi soldiers to feel that they were legitimate actors performing legitimate missions on behalf of a legitimate government, to feel that they were Iraqis first, and Kurds, Arabs, Shi’a, or Sunni second. This was somewhat problematic in 2003-2004 given the de facto American governance, but became easier once we had an Iraqi constitution and government.

Things became very difficult when the increasingly disenfranchised Sunni population launched a new phase of the insurgency in 2006, joining forces with an Iraqi splinter group of al-Qaeda. Many Iraqi units collapsed and the United States was forced to retake the security lead. The failure of Iraqi leadership at all levels and lack of a sense of legitimacy within the ranks was a disastrous combination. We could train a great Iraqi soldier, but we found it very difficult to infuse in him the will to fight and accomplish his mission when he did not feel that he was representing a legitimate government. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki bears the greatest responsibility for the political failures in Iraq and his disenfranchisement of the Iraqi Sunnis.

The problems we see today in Mosul, and increasingly closer to Baghdad, appear to be a repeat performance of 2006. But this time ISIS is a far better organized and equipped adversary for the Iraqi security forces, and ISIS appears to be prevailing. We are obviously at a very dangerous point that could reshape Iraq as we know it.

So, what to do:

Until U.S. forces left Iraq, American and allied advisors helped develop Iraqi Army confidence and coach Iraqi government and military leader behaviors while fostering a sense of being legitimate actors working on behalf of a legitimate government. The least bad option available to the Obama Administration, if asked for assistance, is to field an advisor package similar to what we had in place in the last decade. At every level of Iraqi command, we deployed multi-discipline teams to provide planning and execution advice and training, and assets for combat enablers like intelligence, logistics, and air and ground firepower.

Simultaneously, the United States must develop a regional diplomatic offensive bringing to the table all parties with an interest in the outcome in Iraq. And this includes Iran. ISIS’ offensive in Iraq is a rare moment when the interests of the Middle East’s greatest rivals align. This is a regional problem that should have a regional solution.

A lot of other options, including drone-based attacks or close air support (albeit lacking on-the-ground intelligence for targeting), carry huge political risks for the al-Maliki government and operational risks for the United States. The U.S. presence in Iraq was politically unsustainable in 2011 in Baghdad; the fall of Mosul and Tikrit might make U.S. aid more palatable there now, but politicians will be wary of kinetic operations – especially without sound intelligence for targeting, which would put Iraqi forces and civilians at risk. The United States can help, but it shouldn’t take the lead. We would best serve Iraq today by helping Iraqi Army soldiers believe in themselves and their country.